Tuberculosis. Later, chest

By the mid 19th century living conditions for the urban poor were overcrowded and squalid. Pulmonary tuberculosis, also known as phthysis, consumption and the 'white death', was endemic and was responsible for 20% of all deaths, twice as much as any other cause.

In March 1848 a meeting was held by a group

of City bankers and merchants at the London Tavern in the City of

London to discuss the establishment of a hospital to treat poor people

suffering from the disease who were unable to afford treatment.

Of the 19 present, 13 were Quakers. The group wished to

create a hospital similar to the Hospital

for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest, established in West

London six years earlier. The Royal

Chest Hospital

in City Road, which had opened in 1814, was considered far too small to

accommodate the increasing number of patients in north and east

London. By June the group, under the patronage of Prince Albert,

had raised enough money to open a public dispensary at

6 Liverpool Street while the hospital was being built. The

dispensary was soon overwhelmed with patients and numbers soon had to

be limited to keep the charity solvent.

Plans were drawn up for a 164-bed hospital and, in 1849, the Committee leased a 4-acre site from the Crown estate in Bonner's Field, adjacent to the newly opened Victoria Park. The buildings on the land - the Bishop's Hall and its related structures - were demolished and the land prepared for the new hospital.

In June 1851 Prince Albert laid the foundation stone. The Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, together with Royal connections, had helped to raise the £30,000 necessary.

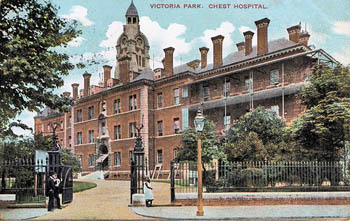

The City of London Hospital for Diseases of the Chest opened in 1855, initially with 80 beds. The 3-storey building was designed, not in the usual Gothic style of the Victorian period, but in the Queen Anne style. It was one of the first hospitals to employ the corridor system. In December Charles Dickens praised the work of the new Hospital in his popular publication 'Household Words'. In 1858 a chapel was built in the grounds, originally as a chapel of ease to the Church of St James-the-Less nearby.

The south wing of the Hospital was completed in 1865. Building began on the final wing, to contain 40 beds, and this was completed in 1871. However, there were no funds to furnish it and it stood empty until 1881, when it finally opened. The Hospital was then complete and had its full complement of 164 beds. Further alterations were made in 1891 and 1899. By this time the Hospital had 46 members of staff.

Treatment of TB was usually limited to simple bed rest and nourishing food. However, by the turn of the century, fresh air was also considered necessary and, in the early 1900s, balconies were added to the wards so that patients could lie in the open air, regardless of weather (if necessary protected by black mackintosh quilts). Fresh air became the treatment of choice, and a sanatorium was opened by the Hospital in Saunderton, Buckinghamshire, for its women and children patients.

Following the Insurance Act, 1911, which required that local authorities established sanatoria for their tuberculous patients, the Hospital became the TB clinic for the Boroughs of Bethnal Green and Hackney in 1912. (TB dispensaries were later established in the two Boroughs in 1916.)

In 1912 the Hospital had 178 beds. It was split into four divisions, with a Sister and two staff nurses in charge of each corridor. The wards were very bright and many of them contained only a few beds. The central heating system was not used; the wards were kept at a low temperature and the windows left wide open. The balconies contained 17 beds for patients undergoing open-air treatment, but all patients were encouraged to be out of doors as much as possible. Male patients, when able, did a certain amount of light work, while the female ones did their own needlework.

Creosote treatments were given in the wards. A light mask containing a piece of lint impregnated with creosote was placed over the patient's nose and mouth and held in place by elastic straps. The patient was required to wear this at all times except at meals. The Hospital basement contained a chamber where creosote inhalations were given daily to patients. The nurse in attendance observed the patient through a glass partition separate from the chamber. In the basement also were the kitchen and its annexes - the larders, storerooms and milk pasteurisation parlour.

During WW1 the Hospital treated injured servicemen from the Western Front, especially those suffering from the effect of gas poisoning, as well as those discharged from the Army because of TB. Other chest diseases - pneumonia and bronchitis, as well as heart disease - were also treated. Twenty beds were reserved for servicemen.

In 1920, to help ease financial difficulties, the Hospital decided to adopt a scale of charges for treatment, and patients were asked to pay 'according to their means'.

In 1923 the Hospital was renamed the City of London Hospital for Diseases of the Heart and Lungs, although it was popularly known as the 'Victoria Park Hospital'. A Pathology Laboratory and research institute opened in 1927, financially supported by the Prudential Assurance Company. In 1928 a surgical block and an X-ray Department were added. X-rays enabled more accurate diagnoses to be made.

In 1931 the Hospital had 131 beds, more than half occupied by tuberculous patients. In 1937 it was renamed again, this time simply as the London Chest Hospital. A new surgical wing was built for major surgery of the chest; surgeons were able to improve on the current surgical interventions - thoracoplasty for TB and lobectomy for bronchiectasis (permanent abnormal dilation of the bronchi).

During WW2 the Hospital cared for both military and civilian patients, with half of its beds being given over to the Emergency Medical Service for air-raid victims. In 1941 the chapel and Nurses' Home were destroyed by bombs. The north wing was badly damaged, with two elderly female patients, both seriously ill, trapped under the fallen masonry. They were rescued by a doctor, along with patients in an adjacent ward, some of whom had to be carried to safety. He was helped by a nurse who had been injured in the explosion but nonetheless stayed to help in the evacuation. In March 1942 the Pathology Department was destroyed in another bombing raid. The 80-year-old collection of specimens and records was destroyed, as well as all the apparatus. A temporary laboratory was set up in the basement pantry and work continued until an open shelter in the grounds could be adopted for a more 'permanent' temporary laboratory. The doors of the bombed lab were salvaged from the wreckage and refitted for this, and benches were made from the teak floorboards; salvaged ward lockers became cupboards. A relief organization, 'Bundles for Britain', helped towards the replacement of the lost equipment. The Hospital remained open throughout the war, with the public funding the necessary repairs.

After the war the Hospital took over some of the emergency hutted wards built at the Three Counties Hospital at Arlesey as extra accommodation for TB patients (this arrangement ceased in 1962).

In 1949 it joined the NHS with 135 beds, becoming a teaching hospital, together with the Brompton Hospital. The Boards of Governors were reconstituted to cover both hospitals.

In 1963 twin operating theatres were installed especially for the surgical treatment of pulmonary TB. The introduction of penicillin after the war had led to a dramatic decline in the incidence of the disease, and the Hospital began to treat patients with heart disease, especially of the coronary arteries. It was one of the first in the United Kingdom to undertake open heart surgery, pioneering the use of the heart-lung bypass machine.

By 1970 it had gained an international reputation for the treatment of heart and lung disease, especially in coronary artery bypass surgery.

In 1974, following a major NHS reorganization, the Hospital became part of a Special Health Authority - the National Chest and Heart Hospitals - along with the Brompton Hospital and Frimley Hospital. In 1975 its Out-Patients Department was extended and a Teaching Centre built.

During the 1980s the cardiothoracic surgery unit expanded when new operating theatres and intensive care facilities were opened. In 1983 a new block containing wards and laboratories was built. In 1986 a new library was added.

In 1994, following publication of the Tomlinson Report, 1992, the Hospital joined with St Bartholomew's Hospital and the Royal London Hospital to form the Royal Hospitals NHS Trust (in 1999 this was renamed the Barts and The London NHS Trust).

The Hospital has continued to develop specialised units. Over the past decade cardiac catherisation laboratories, an intensive care unit with 10 beds and three new operating theatres have opened. In 2003 a new unit - the Jack Turner Cystic Fibrosis Unit - was established for the care and treatment of adult sufferers of the condition. A new Respiratory Function Unit opened in 2005 and, in 2007, a new Heart Attack Centre, the largest in Britain.

In 2009 a state-of-the-art cardiac CT scanner was installed.

Present status (December 2009)

The Hospital is still operational but some of its services will move to the new Cardiac Centre at St Bartholomew's Hospital, currently being built, along with the new PFI-funded 900-bed Royal London Hospital. The project is due to completed by 2012.

Once thought to be under control, TB has now returned as a serious health problem, with new strains being resistant to drug treatment. The 'Chest Hospital', as it is referred to locally, continues to treat TB patients, some with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

Update: February 2015

The Hospital building and its 4-acre site is due to be sold to developers in December 2015.

Update: June 2015

The Hospital closed in April 2015. Services moved to the new Barts Heart Centre at St Bartholomew's Hospital.

The Hospital as seen from the corner of Bonner Road and Approach Road (left) and from Approach Road (right).

The western elevation of the original 'Queen Anne' red brick building with its bell tower.

The former main entrance.

The windows of the original building are decorated with charming statues.

The southern wing of the original building has been extended over the years (left). The current main entrance is on the southern side of the extension (right).

The south side of the Hospital has the current main entrance on the left (left) and the entrance to the Out-Patients Department on the right (right).

The south side of the Hospital as seen from St James's Road.

Hospital buildings along Bonner Road.

The front garden of the Hospital on the corner of Bonner Road and Approach Road.

The Hospital in 1905.

Bishop Bonner died in prison in 1569, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

Williams CT 1898 The open-air treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis as practised in German sanatoria. British Medical Journal (May 21), 1309.

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com

www.aim25.ac.uk

www.bartshealth.nhs.uk

www.british-history.ac.uk

www.eastlondonadvertiser.co.uk

www.eastlondonpostcard.co.uk

www.geograph.org.uk

www.gov.uk

www.guardian.co.uk

www.hsj.co.uk

www.lung.ca

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

www.nowpublic.com

www.rlhleagueofnurses.org.uk

www.theguardian.com

www.threecountiesasylum.co.uk

Return to home page