Tuberculosis. Later, general, cardiothoracic

The National Insurance Act, 1911, compelled local authorities to establish TB hospitals and, by 1920, the Middlesex County Council (MCC) had an urgent need for TB beds. It had purchased a piece of land in Essex on which to build a sanatorium, but the outbreak of war delayed the project. Until its own sanatorium could be built, the MCC made arrangements to send its patients to Clare Hall Hospital.

The No. 1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital on the Harefield Park estate had closed in 1919, but the owners of the estate, the Billyard-Leakes, who had been living at the nearby Black Jack's Mill, felt unable to move back into their old home. Instead, they sold the estate for £20,000 to the MCC.

Harefield, being one of the highest points in Middlesex, some 290 feet (90 metres) above sea-level, could provide abundant fresh air and sunlight - ideal for the favoured open air treatment for the disease. The MCC sold their site in Essex and the money was put towards the purchase of Harefield Park estate.

Work began on the site in 1920. The Australian huts remained, but they were unsuitable for TB patients, being too close together. Most of them were demolished but several were re-used in a different configuration, which enabled the male patients to be segregated from the female, and the children from the adults. The mortuary and the chapel remained.

The Harefield Sanatorium opened in October 1921 with 250 beds. It looked quite different from the No. 1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital. The patients were accommodated in six large single-story huts (pavilions). Male patients were at the north of the site, at least half a mile from the entrance. Females were to the south, while the children's wards were nearest to the entrance, with that for boys at the east end and for girls at the west end. A school room was nearby, connected to the children's hut by a covered walkway. The former coach house became the Observation Ward, where new patients were admitted while it was confirmed that they had pulmonary TB.

The House (now known as The Mansion) was used for medical staff quarters. Matron resided in her own wooden bungalow, while the Nurses' Home consisted of six huts with cubicles. The nursing staff comprised 11 Sisters, 17 Staff Nurses and 23 probationers. Altogether the Sanatorium had 110 staff, including a cook, a laundress, a seamstress, an engineer, a stoker, a lodge keeper and an ambulance driver. However, the isolated location and crude living conditions made recruitment of staff difficult.

The Sanatorium had its own farm and orchards, making it relatively self-sufficient. Geese, turkeys and 3,000 laying hens were kept, as well as pigs and a few goats. The kitchen garden provided salad and vegetables.

In 1932 a new Nurses' Home was built to the south of the old one. In 1933 it was decided to replace the wooden huts with permanent brick buildings on the site of the female ward pavilions. The patients were moved to the old Nurses' Home and the Sanatorium remained operational when building work began in 1935. It was completed in 1937, the last hospital to be built in Britain before WW2.

The Harefield County Sanatorium was officially opened in October 1937 by the Duke of Gloucester. The main building, in a modern 'international' style, was crossbow in shape - a central block with curved, angled wings to either side of it - across a north-south axis. It had 378 beds in the two 3-storey wings, which faced south towards the village. The central section contained the administrative offices, treatment rooms, an X-ray Department and, as the MCC were aware of the future role of surgery in the treatment of TB, an operating theatre. (Reputedly, the Sanatorium was one of the first places to treat TB patients with artificial pneumothorax in January 1939.) Behind the central block, in a separate building to the north, were located the central kitchen and the main dining room. The building also contained a concert hall and a recessed chapel at one end. The Observation Ward, utilities and services were located to the north of the main block. The Sanatorium had its own water supply and generated its own electrivity.

The new buildings were connected with paved roads and there was a new entrance in Hill End Road. New staff accommodation had been built to the far north of the site. The Lodge to the old entrance had been pulled down and the entrance was pedestrianised.

At the outbreak of WW2 the Sanatorium became the Harefield Emergency Hospital, an Emergency Medical Service base hospital for St Mary's Hospital in Praed Street. Thirteen prefabricated huts of corrugated iron lined with asbestos and with pitched roofs were built. Each contained 24 beds. The huts were heated by three coke stoves - one at each end of the hut and one in the middle. The Hospital would contain 464 casualty beds. In September 1939, just as the patients had been transferred from St Mary's Hospital, an outbreak of meningococcal meningitis occurred at the Harefield site. Fortunately, a new drug - sulphanilamide - was available and no-one died (the infection previously had had a 70-90% mortality).

During 1940 sixteen more huts were added, made of concrete with flat roofs. An Almoner's Department was established. In November the Hospital received a large influx of patients - servicemen from the British Expeditionary Force in France who had contracted TB. Little could be done and mortality was high.

During the Blitz in 1941 air-raid victims in central London were treated at St Mary's Hospital and then bussed out to Harefield. Later, military cases were flown to Northolt to be transferred to Harefield. Dealing with war casualties, the Hospital enlarged its scope for general and thoracic surgery.

At its peak the Hospital had 1200 beds. Patients included Polish servicemen and Free French forces. Later, German naval prisoners-of-war also received treatment.

Matron's old wooden bungalow was used as a 'cottage laboratory' by Prof. Alexander Fleming while he studied the effect of penicillin on TB.

The Hospital received no bomb damage during the war and, in 1945, St Mary's Hospital returned to Praed Street. By 1945 penicillin had become generally available for the treatment of TB and other infections. The government had undertaken to provide treatment in Military Units for all servicemen with TB, and one such Unit was established at Harefield. Located at the north of the site, it had 6 wards with 24 beds in each.

Very little cardiac surgery had been possible during the war, but the first thoracic surgeon appointed to the Hospital, Mr Thomas Holmes Sellors, performed the first valvotomy, an operation for the direct relief of pulmonary stenosis in a patient with Fallot's tetralogy (a congenital heart defect) in December 1947. Pioneering surgical techniques were also developed to treat disease and injury of the oesophagus. A service to treat carcinoma of the oesophagus was established in the late 1940s.

In 1948 the Hospital joined the NHS under the control of the Harefield and Northwood Hospital Group, part of the North West Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board. It was renamed Harefield Hospital and became a general hospital but still had a Thoracic Surgery Unit, now treating all kinds of chest diseases (during the 1950s, as the incidence of TB fell, the TB Clinics were renamed Chest Clinics).

By the 1960s the farm, piggery and kitchen garden had gone. The 'cottage laboratory' had been demolished and TB had all but disappeared. The Hospital became one of two hospitals (the other was Clare Hall Hospital) under the control of the North West Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board which treated chest diseases, as well as medical and surgical general cases.

In 1960 a Mayo-Gibbon heart-lung machine was purchased and first used in 1961 during a valvotomy on a 12-year-old girl with Fallot's tetralogy. A Respiratory Physiology Department was established in 1961. In 1964 a new Physiotherapy Department opened, and work began to build a new X-ray Department and a twin operating theatre suite just south of the east ward wing. A new Pathology Department opened in 1965.

The thoracic work became more specialised. By 1967 the Thoracic Surgery Unit had 80 beds. A pacemaker service was established. A new road and car park were built on the north side of the site. The new X-ray Department and operating theatres opened in July.

By the early 1970s, while thoracic patients were still being investigated and treated, the number of cardiac operations had trebled. The Hospital became recognised as the Regional cardiothoracic centre. In 1973 Mr. Magdi Yacoub was appointed as a consultant cardiac surgeon and established a Paediatric Surgical Unit with 9 beds. Clare Hall Hospital closed in 1974 and its thoracic work transferred to Harefield Hospital, which at this time had 400 beds.

In 1976 a two-stage operation was pioneered for anatomical correction in children with 'transposition of the great vessels' (the aorta and pulmonary artery leave the wrong side of the heart). (Usually undertaken in the first few weeks of a child's life, the first one-stage operation on a neonate was performed in 1982.) By 1979, although the Hospital still accommodated general medical and surgical cases, it was increasingly specialising in cardiothoracic surgery and medicine.

In 1980 the X-ray Department was extended at the cost of £500,000. The new unit was opened by the Minister of Health and contained equipment for special investigations and interventions, such as cardiac catheter, angiography and ultrasound. In 1980, under the leadership of Magdi Yacoub, surgeons performed Harefield's first heart transplant. In 1983 Mr. Yacoub performed the first combined heart and lung transplant worldwide (lung transplant alone was less successful than a heart-lung transplant). The following year a baby, less than one month old, received a heart transplant. In 1987 the first 'domino' procedure was undertaken, whereby a patient with cystic fibrosis (who had a healthy heart) underwent a heart-lung transplant, while a second patient received the first patient's heart. In 1988 the Eric Morecambe Department of Cardiology and a new Intensive Care unit were opened by Sarah Ferguson, the Duchess of York. By this time the Hospital had 172 beds. In July 1989 the Princess Royal opened the Playdrome and extension to the children's ward.

In 1995 the Hospital, together with the National Heart and Lung Institute of Imperial College, pioneered the development of a device - an artificial left ventricle - to assist the heart to pump.

In 1998 the Hospital merged with the Royal Brompton Hospital to form the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Trust.

In 2000 the Harefield Research Foundation was established to continue the work of Prof. Yacoub, who was knighted in 1991. (Located in the Heart Science Centre, it was renamed the Magdi Yacoub Institute in February 2004.)

In 2003 the Anzac Centre opened. Built at a cost of £4m, it replaced some of the oldest accommodation at the Hospital. It contains the Out-Patients Department, the Respiratory Physiology Department (for lung function tests), the Echocardiology and Nuclear Medicine Departments, the transplant clinic and two cardiac operating theatres.Present status (March 2010)

Harefield Hospital remains operational. The Grade II*- listed mansion survives, as well as its two flanking buildings (the coach house and stables).

The main gate with a police station on the right.

The central block with the main entrance to the Hospital (left). The curve of the wings can just be discerned (right).

The north block contains the chapel and the canteen ('The Hungry Hare') (left) . Looking west, the main entrance is on the left, with the north block on the right (right).

The second phase of the new Harefield Heart Science Centre opened in 2002, the first having opened in 1992.

Sculptural art at Harefield: a statue by Anthony Gormley (left) was unveiled by Gordon Brown, Chancellor of the Exchequer, in March 2005. The statue is located on the roof of the Heart Science Centre. Mr Brown returned again in November 2008, now the Prime Minister, to unveil a statue of Prometheus (right), a gift of members of the Praxiteleion, a group of Greek hospitals and diagnostic centres engaged in similar work to the Magdi Yacoub Institute.

The refurbished Thoracic Unit under construction to the south of the main hospital.

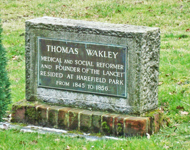

Near the main gate is a monument to Thomas Wakley, founder of The Lancet, who lived at the estate from 1845-1856, when it was known as Belhamonds. Wakley was a great figure in the world of medicine at the time and was instrumental in setting up the Royal College of Surgeons in 1843 and, in 1858, the General Council of Medical Education and Registration (since 1951 known as the General Medical Council).

Hospital buildings at the north of the site.

The south entrance leading to Harefield Health Centre.

The Anzac garden at the southeast corner of the lake.

The land to the north of the current Hospital once housed the temporary pavilions for male patients suffering from tuberculosis. The huts were demolished when the permanent Hospital was erected, but rebuilt during WW2 as part of the Emergency Medical Service Hospital. They survived until the 1980s, when the area became a Medipark. In February 2010 developers began to clear the land with a view to building an apartment block on the site.

Cobbett L 1930 The decline of tuberculosis and the increase in its mortality during the war. Journal of Hygiene 30, 79-103.

Hollman A, Treasure T 1998 Pulmonary valvotomy - 50 years ago. The Lancet 352 (9145), 1956.

Shepherd MP 1990 Heart of Harefield. London, Quiller Press.

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com

www.aim25.ac.uk

www.british-history.ac.uk

www.flickr.com

www.hillingdon.gov.uk

www.rbht.nhs.uk

Return to home page